The University of Oxford's Women's Colleges

Lady Margaret Hall

By Oliver Mahony

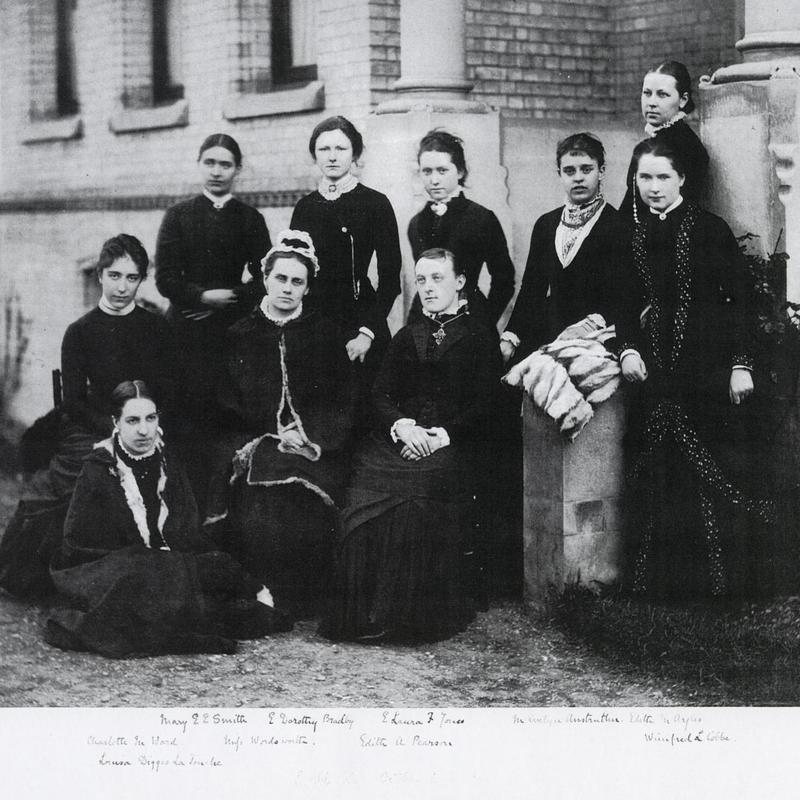

Lady Margaret Hall was founded in 1878 as the first higher educational institution open to women in Oxford. It was founded by Bishop Edward Talbot, Warden of Keble College and his wife Lavinia. It was as much a religious High Anglican undertaking as an educational one. This led to some members of the founding Council splitting away and reconvening on Woodstock Road to establish the non-denominational Somerville College the following year. Talbot and the early council chose Elizabeth Wordsworth as the first Principal, great-niece of the poet William, who was steadfast in her High Anglican commitment. Wordsworth named the Hall after Lady Margaret Beaufort, the mother of King Henry VII, a notable patron of learning. The first nine students took up residence in the white villa house at the northern tip of Norham Gardens in October 1879. This house which was leased from St John’s College became known as Old Hall.

Student Edith Pearson writing in the December 1908 edition of The Brown Book about her experience of Old Hall was less than complimentary of the early accommodation:

‘There were nine of us Students in the first term. We lived in the dear old white house, we could see the landscape round nearly all the windows because they fitted so badly, we moved about from room to room according to which chimney smoked worst on any particular day…There was no way of warming the stairs, which abounded in draughts.’

Pearson was however complimentary about the close-knit community atmosphere that Wordsworth fostered during these early years. Wordsworth, although undoubtedly a pioneer in opening educational opportunities to women (she went on to found St Hugh’s in 1888) was memorably characterised as a ‘reluctant pioneer’ by her biographer Georgina Battiscombe. Wordsworth was not convinced of the wisdom of awarding degrees to women and believed in preparing women for marriage and domestic life. Despite this, key alumni of the Hall at this time were at the forefront of the fight for female emancipation, including suffragist Kathleen Courtney (LMH 1897) and preacher Maude Royden (LMH 1896). Yet over the thirty years she was Principal she oversaw major expansion of the site. In 1881 New Old Hall, designed by Basil Champneys opened as the first extension to the Hall. Wordsworth also oversaw the building of Wordsworth in 1896, named after her father Christopher, the Bishop of Lincoln, and finally in 1910 the elegant Talbot Building, designed by Reginald Blomfield. The heart of the early Hall had now moved, from the domestic setting of Old Hall to the oak panelled dining hall and new Library offered in the Talbot Building. It would continue to grow after 1920 with the addition of new buildings and increased student numbers.

Somerville College

By Katherine O’Donnell

Somerville College was founded in 1879, one of the three Oxford women’s societies to open their doors to students in October of that year, along with Lady Margaret Hall and the Society of Home Students, later St Anne’s. Classes and teaching for women had expanded in Oxford during the 1870s. To accommodate the increasing demand, a ‘ladies’ Hall’ was proposed, which would provide accommodation for students from outside the city, with classes organised by the AEW (Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women). However, the original committee’s insistence that applicants had to be members of the Anglican church led to a schism. A breakaway group, under the philosopher T.H. Green, drew up proposals for a second, non-denominational Hall for women. It was named Somerville Hall, in honour of the Scottish mathematician, scientist and supporter of women’s education, Mary Somerville.

Many members of the founding committee were Liberals and the Hall’s first Principal came from a family with a background in Liberal politics and public service. Madeleine Shaw Lefevre initially took the post for one year, but remained as Principal for the following decade. The founding committee took a five- year lease on Walton House, a stone villa set in three acres of gardens on the Woodstock Road, owned by St John’s College. Somerville’s first intake of students in 1879 numbered 12, but from the outset it was apparent that the buildings could not accommodate all the members of the Hall, and within months negotiations were underway for the purchase of Walton House, to be funded by donations and a loan. Through her connections, her considered approach and her personal charm, Madeleine Shaw Lefevre helped build support for women’s education in Oxford and among the parents of prospective students. A new building, West, was constructed in 1885 and by the time Agnes Maitland took over as Principal in 1889, there were 35 students in residence.

Agnes Maitland had a background in home economics and had taught and published on the subject. She was a staunch Liberal and gifted administrator, who set out to build upon the sound foundations laid down by her predecessor. Under Agnes Maitland, the Hall progressed academically: student numbers grew to 86 and as applications started to exceed available places, qualifying examinations became a requirement for entry. The teaching staff increased, conditions of employment for tutors were formulated (including the introduction of paid sabbaticals) and the first research fellowship was established. The Hall was permitted to adopt the Somerville family crest and motto and, in 1894, Somerville Hall was renamed Somerville College, confirming its aspirations to be more than a Hall of residence. House and West were extended further and, in 1904, the college library was opened, the first of the women’s colleges to have a purpose-built library and one of the first libraries built in any Oxford college primarily for the use of the students. Gifts of books to the college included the library of Amelia Edwards, writer and founder of the Egypt Exploration Society, and the London library of John Stuart Mill.

Agnes Maitland died in 1906 and in 1907 one of her former students became the college’s third Principal. Emily Penrose had come up to Somerville in 1889 at the age of 31. She was the first woman to take a First in Greats (Classics) at Oxford. In 1892 she was appointed Principal and lecturer in ancient history at Bedford College London, from 1898 to 1907 she was the Principal of Royal Holloway College, and in both posts she honed her skills in university politics and administration, being active on the London University Senate. On returning to Oxford, she built on Agnes Maitland’s work to consolidate the college’s academic standing and raise standards still further. In 1908, Somerville was the first of the women’s colleges to introduce an entrance examination for all applicants. Emily Penrose also insisted that students should observe all the qualifying requirements of degrees, such as residence, and take the honours course whenever possible so that, once women were admitted to degrees, many former students would be eligible to graduate. In 1912, Somerville was the first of the women’s colleges to attract endowment for research. Those who attended meetings at which Emily Penrose presided or participated found them an education in how to get things done. In almost all matters, she was cautious and considered, weighing up the benefits of a course of action and its impact on the overarching aim - the admission of women to degrees. She abandoned this approach in only one matter: Somerville was a college of suffragists, and Emily Penrose allowed suffrage meetings to be held there, even when supporters of the college, with different views on votes for women, withdrew their funding in protest.

In April 1915, the War Office took over the Somerville site for use as a military hospital and the college moved to St Mary Hall Quad in Oriel, returning to the Woodstock Road in 1919. During the First World War, the position of women in Oxford changed radically, as the absence of male academics and undergraduates led to a greater dependence on women to keep the University functioning. By the time Somerville returned to the Woodstock Road site, membership of the University was just a few months away and thanks to Emily Penrose’s foresight, some 300 Somervillians were qualified to graduate.

From Home-Students to St Anne’s College

By Duncan Jones and Clare White

In 1878 when the Association for the Education of Women in Oxford (AEW) was founded, it represented the interests of women in Oxford who were permitted to work independently towards University level examinations. When Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville Hall were founded in 1879, there were some 25 students left over who lived at home with their parents (mostly University dons and their wives) or relatives in Oxford.

The first secretary of the AEW., Charlotte Green, made initial arrangements for the supervision of these students. From 1883 it was Bertha Johnson, the wife of the historian, the Reverend Arthur Johnson, who oversaw and planned their studies.

These ‘home’ students were first identified as such in 1890 following the first mandatory registrations in 1888. The Home-Students gained their first official Principal (Mrs Johnson) in 1893, though it would be easy to argue that she had been Principal in everything but name for 10 years already. In 1898, the AEW. Council adopted the term Society of Oxford Home-Students for the group and in 1899 they gained their first common room, the first in a series of simple rented premises around Oxford. The most well-known of these was on Ship Street and gave its name to the alumnae publication The Ship which began in 1911 and continues to this day.

Until the existence of a common room, and indeed well after it, Mrs Johnson administered the Home-Students entirely from her living room at 22 Norham Gardens.

In 1910, the University established the new Delegacy for Women Students and Mrs Johnson was again appointed as Principal for the Home-Students, this time by a Decree of Convocation. The Decree made her the only ex-officio female member of the Delegacy and the first woman to be appointed by the University to any office or Delegacy.

The Society appointed its first tutors in 1913; appointments which, like Mrs Johnson’s, carried some status but no salary. A gradual untangling of the AEW. and the Delegacy of Women Students saw the Home-Students find their own secretary, office and lecture rooms. It was not until 1921, with Mrs Johnson retired and the AEW. disbanded, that they found any sort of permanent home. This was at 1 Jowett Walk, rented from the University and home to the Society and its library until 1937, when it partially moved to the current Woodstock Road site.

By the early 1940s there was growing pressure from the undergraduates and alumnae of the Society for a change of name. “Home-Students” no longer seemed appropriate when the majority of students lived in hostels or large houses managed by hostesses. Furthermore the name caused confusion in the world of employment beyond Oxford, with the belief that the Society was either a correspondence college allowing women to take some sort of external degree, or that it was a school of domestic science. The pressure succeeded and in 1942 the Society of Oxford Home-Students became St Anne’s Society. Ten years later, the Society was granted its Charter of Incorporation and became St Anne’s College.

St Hugh’s College

By Amanda Ingram

In a letter to the Guardian in May 1886, Elizabeth Wordsworth, Principal of Lady Margaret Hall (LMH), announced her intention of opening

'A small home-like house' for young women who wished to study in Oxford but who found 'the charges at the present Halls at Oxford and Cambridge . . . beyond their means.’

These students would follow the same academic course as those at the two existing women’s colleges in Oxford but for lower fees, economy being achieved by frugal living and smaller accommodation. Miss Wordsworth named the new Hall after St Hugh of Avalon as a tribute to her father, who, like St Hugh, had been Bishop of Lincoln.

She appointed Annie Moberly as first Principal - the two had probably met when Miss Wordsworth's brother succeeded Miss Moberly's father as Bishop of Salisbury. Miss Wordsworth seems to have seen the post as one of housekeeper but Miss Moberly clearly saw herself more as Principal of a college, albeit an embryonic one. She was to a large extent responsible for the transformation of St Hugh's from a small private Hall of residence into a thriving college.

Four students registered at St Hugh's in 1886 and lived in a semi-detached house at 25 Norham Road. A large percentage of the young women who came to St Hugh's in the early years were the daughters of clergymen, most of the other fathers were in the professional middle classes and over half of the students went on to work as schoolteachers and headmistresses. In 1887, Miss Wordsworth rented 24 Norham Road and the number of St Hugh's students rose to ten. Then, in 1888, she bought the leasehold of 17 Norham Gardens which could accommodate twelve or thirteen students; a new wing was added to it in 1892, housing a further twelve students. By 1910 there were 42 students at St Hugh's, living in five North Oxford houses and taught by seven tutors.

In these early years, St Hugh's was very much a private venture of Miss Wordsworth with no constitution and no governing body. A Committee was established in 1891, but was not given any specific powers. In 1893, Miss Wordsworth planned to change St Hugh's from an independent Hall of residence into a hostel for students of LMH but the LMH Council rejected the proposal. In 1895, St Hugh's property was vested in a Trust, which, joining forces with the St Hugh's Committee, became a fully-fledged Council and Governing Body. In 1911, the Trust was wound up and St Hugh's became a registered company, now officially described for the first time as a College.

In 1897, wealthy heiress Clara Mordan visited St Hugh's. She was much impressed by Miss Moberly and the following day sent her a cheque for £1000 to endow a scholarship, promising further financial help should College need it. She visited St Hugh's regularly and was co-opted on to College Council in 1902, becoming a trustee in 1907. In 1912 the College bought a nearby property called ‘The Mount’. This was demolished and replaced by the first college building (now known as ‘Main Building’), which was to accommodate 71 students. When building progress was threatened by the outbreak of war in 1914, Clara Mordan's generous legacy allowed it to be completed and it was opened in January 1916.

The College’s second Principal, Eleanor Jourdain, was appointed in 1915. A close friend of Miss Moberly, the two ladies went to Paris together in 1901 and shared an 'adventure' at Versailles, where they believed they had travelled back to the time of the French Revolution – a supernatural episode which still fascinates people today. Miss Jourdain was an acclaimed teacher, headmistress and Dante scholar and had been appointed Vice-Principal in 1902. She enjoyed a high reputation in the University at large – she was among the first women to be appointed to a university lectureship and was the first to examine undergraduates in the Final Honours School. It was also during her time in office that women were, in 1920, admitted as full members of the University.

Sadly, Miss Jourdain’s tenure as Principal was to end on a tragic note a few years later. Although she proved an able administrator, she was autocratic by nature and was unwilling to allow the tutors to become involved in the running of College. The ensuing arguments (still known in College as 'The Row') came to a head in 1923, when the Principal decided not to renew the contract of the history tutor, Cecilia Ady, whom she regarded as the leader of what she saw as the opposition. In a gesture of support for Miss Ady, the St Hugh's tutors resigned en bloc, and tutors in other colleges refused to teach St Hugh's students. College Council asked the Chancellor of the University, Lord Curzon, to adjudicate, and he found in favour of the tutors. Miss Jourdain seems not to have anticipated this outcome, and on 6 April 1924 (four days after the publication of the Chancellor's report in the University Gazette), suffered a fatal heart attack. Although this episode resulted in the modernisation of the administration of the College, it also remained an extremely sensitive subject for many years.

St Hilda’s College

By Oliver Mahony

In 1889 Miss Dorothea Beale, Principal of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, wrote to the Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women in Oxford (AEW) to tell them that she intended to open a house for women to study in Oxford. It was be named after St Hilda ( 614-680), head of Whitby Abbey, and was intended to offer her best scholars and younger tutors at Cheltenham Ladies College a base to avail themselves of the new intellectual opportunities Oxford offered without pressing examination on them.

The proposal was met with opposition by the AEW and the other Halls alike. The AEW was worried about the effects of an institution outside their sphere of influence. They responded that such an institution would damage the interests of the Association by

‘lowering the standard of work, & tolerating or encouraging dilettantism’ and ‘by making it easy for “students” to come up to Oxford under less rigid rules … thus introducing a class of students who would add considerably to the difficulty of keeping up a standard of good manners’.

Miss Beale was told that her plan was not acceptable.

In The Cheltenham Ladies' College Magazine in Spring 1893 Miss Beale published a photograph of her newly acquired Georgian base in Oxford, Cowley House, and a statement of her intentions for it. With no actual means of preventing her, the AEW finally offered its support for its foundation. However, the establishment of a formal financial and administrative structure was required before St. Hilda's was accepted as a recognized Hall for women in 1896.

The new institution started with seven students and although at this early stage it was mainly intended as a house for pupils of Cheltenham Ladies College, by 1904 it had welcomed some forty students who had been educated away from Cheltenham. In 1893 Miss Beale appointed Mrs. Esther Elizabeth Burrows as first Principal. She was succeeded in 1910 by her daughter Christine who went on to become the Principal of the Society of Oxford Home-Students in 1921.

During these early years there were profound structural changes to governance. In 1897 the Hall became an incorporated company with its own governing council. In 1901 St Hilda's Oxford was amalgamated with another Beale project, St Hilda's Cheltenham, to form St Hilda's Incorporated College. In 1910 the University formally acknowledged the existence of female students in Oxford by forming the Delegacy for Women Students, and St. Hilda's became a recognized society for women students.

There were also changes physically. Alongside extensions to Cowley House (which became known as Hall Building) St. Hilda’s acquired a house on an adjacent site, Cowley Grange. This had been built in the 1870’s as a house for Christ Church Chemistry tutor Augustus Veron Harcourt. It was subsequently sold to the Church Education Authority who oversaw the Cherwell Hall teacher training college there until St Hilda’s took over the site in 1920, the year that women were finally recognised by the University.