Degrees for Women: The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Introduction

In 1919… the House of Commons passed the Second Reading of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill, with its comprehensive opening words: “A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation.”1

So wrote Vera Brittain in 1935, giving full credit to the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act for degrees for women at Oxford, achieved while she was an undergraduate in 1920. Passed on 23 December 1919, the Act allowed women to become solicitors, barristers, magistrates and jurors for the first time. It also enabled women to enter other professions, such as accountancy, and admitted women to the higher ranks of parts of the civil service. Although undoubtedly a landmark for women, there were some important provisos which limited its effect, and many obstacles remained, such as the bar on married women working in many professions.2

The 1919 Act and universities

Nothing in the statutes or charter of any university shall be deemed to preclude the authorities of such university from making such provision as they shall think fit for the admission of women to membership thereof, or to any degree, right, or privilege therein or in connection therewith.3

The author of this section was Major John Waller Hills MP, who introduced it as an amendment during committee stage in the House of Commons on 27 October 1919. Hills declared, 'Apparently some doubt exists whether universities have the power under their Statutes or Charters to admit women to degrees, and my Clause is designed to remove that doubt’.4 In fact, by 1919 all universities in the UK and Ireland already admitted women to degrees except for Oxford and Cambridge. Hills' amendment was therefore aimed at Oxbridge.

Hills was a Balliol graduate, a backbench Liberal Unionist (later Conservative) MP, and a great friend to women's campaigning organisations. He made strong arguments on various aspects of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill during its passage, including against the marriage bar and civil service restrictions. Although many of Hills' arguments had limited success, the universities amendment was perhaps the least controversial. Only one MP objected, Sir John Butcher, who complained that universities had not been consulted. The Solicitor-General, Sir Ernest Pollock, accepted Hills' amendment, saying, 'This Clause merely takes away… a bar. We are not giving any directions to any university that they shall make provisions’.5 This was accurate: although Oxford admitted women to degrees within a year, Cambridge did not follow until 1948.

The Fight for Degrees

The fight for Degrees for Women at Oxford had always been closely connected with the feminist movement as a whole, and in 1919 it shared in the impetus given everywhere to the women's cause by the ending of the War. Except for Lord Curzon, Lord Birkenhead and Mrs Humphry Ward, no anti-feminists of any importance appeared to be left in the country...6

So why did Oxford take the opportunity presented by the Act so swiftly? Pioneering women campaigners had succeeded in establishing women's halls and colleges in Oxford from the 1870s, and taking examinations from the 1880s. Admission to full membership and degrees was an obvious next step. However, in 1896, a proposal to award Diplomas to women who had passed all requirements for BA degrees was rejected by Congregation, Oxford's governing body.

The cause then found a perhaps rather unexpected ally. Brittain might have been surprised to learn that well-known anti-feminist Lord Curzon proposed that women be admitted to degrees in a reforming memorandum in 1909, when the struggle for women's suffrage was in full swing. As Chancellor of Oxford University (1907-1925), he argued it would be in the interests of women students, teachers and the University itself. He drew the line at full equality, opposing women as members of university governing bodies. As a die-hard opponent of women's suffrage (he became President of the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage in 1912), he was also clear that degrees would be a private reward for a woman's industry and learning, rather than a grant of any public right or duty.7

In 1918 suffrage was largely taken out of the argument, when women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications were given the vote.8 Curzon was still Chancellor, and the question of admitting women to degrees came to the fore again. The University was advised to obtain sanction in the form of a special Act of Parliament.9 This was rendered unnecessary by the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act in December 1919.

The Statute for Degrees for Women

The statute for Degrees for Women has just been published; in it they give us absolutely everything we ask for and it will be discussed at the beginning of next term… which means that when I do my Finals I shall also get my Degree and you will see me going about in a mortar-board and gown...10

On 17 February 1920, Congregation passed the preamble of a statute admitting women to matriculation and to degrees. It was introduced by Professor W M Geldart, who observed that women had previously been described as 'guests of the University. It was now time they should become full members of the family.'11 Geldart also argued that now that the question of the franchise was settled, 'there was no longer good ground for refusing women graduates admission', and that there would be a considerable increase of income to the University.12

Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby were listening to Geldart and his colleagues, 'our hearts surging warm with hero-worship... and realised from the small opposition encountered by their speeches that the battle was almost won’.13 However, the statute was not completely without opposition. On 9 March attempts were made to exclude women from serving on delegacies, boards and committees and from acting as examiners, by opponents who expressed 'fear that women would come to be predominant in the University'. These amendments were rejected.14

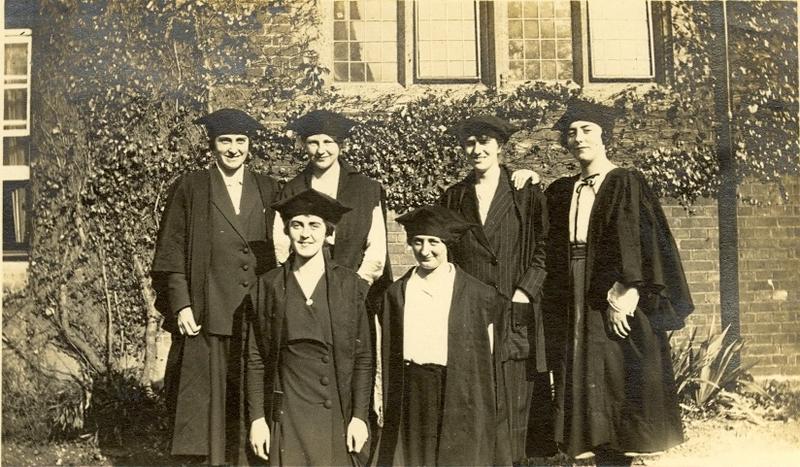

The statute was passed by Congregation on 4 May and by Convocation (all graduates of the university) on 11 May 1920.15 It admitted women to matriculation, degrees16 and full membership of the University. About 110 women, including Brittain and Holtby, matriculated on 7 October 1920, and the first 50 women graduates were retrospectively awarded their degrees on 14 October. This was a huge landmark for Oxford women, and a radical moment, as Brittain reflected:

Even the unchanging passivity of Oxford beneath the hand of the centuries must surely, I thought, be a little stirred by the sight of the women's gowns and caps… the visible signs of a profound revolution.17

[1] Vera Brittain, Testament of youth: an autobiographical study of the years 1900-1925 (London: Virago, 2004; first published 1935), pp. 504-508.

[2] You can view the Act and related documents on the Parliament website: https://www.parliament.uk/sdra1919 . For a fuller exploration, see: Mari Takayanagi, 'Sacred year or broken reed? The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919', Women's History Review, 2019 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09612025.2019.1702782 [accessed 14 April 2020].

[3] Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, c. 71, s. 3.

[4] HC Deb 27 October 1919 vol 120 cc398-400.

[5] HC Deb 27 October 1919 vol 120 cc398-400.

[6] Brittain, Testament of youth.

[7] Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Principles & Methods of University Reform (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909), pp. 193-200.

[8] For a summary, see: Mari Takayanagi, “The Representation of the People Act 1918: A Democratic Milestone in the UK and Ireland” (OxHRH Blog, 6 February 2018), <http://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/the-representation-of-the-people-act-1918-a-dem... [accessed 14 April 2020]

[9] Ed. H E Salter and Mary D Lobel, 'The University of Oxford', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford, (London, 1954), pp. 1-38. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp1-38 [accessed 14 April 2020].

[10] Brittain, Testament of youth, quoting a letter to her mother in November 1919.

[11] The Times, 18 Feb 1920.

[12] The Guardian, 18 Feb 1920. https://www.theguardian.com/gnmeducationcentre/2019/oct/08/october-1920-women-granted-full-membership-of-oxford-university#maincontent [accessed 14 April 2020]

[13] Brittain, Testament of youth.

[14] The Times, 10 March 1920.

[15] The Times, 5 and 12 May 1920.

[16] Except Theology, which had to wait until 1935. Salter and Lobel.

[17] Brittain, Testament of youth.