‘Exhibitions remind us all that history doesn’t just happen. It is made as we live it and shaped by how we interpret it.’ Professor Senia Paseta on the curation of Sappho to Suffrage: Women Who Dared

Taking something of a break from my usual job as a tutor in History, I have spent a good proportion of the last two years curating Sappho to Suffrage: Women who Dared. This new exhibition in the Weston Library highlights items from the Bodleian’s holdings which were made, written, owned or commissioned by women. As the Bodleian holds more than 13 million items from across the ages and the globe, one might think that the chief difficulty in curating such an exhibition would be ruling items out rather than in. In fact, I visited a number of departments which could offer me very few (and even in some cases no) suggestions for inclusion. All could offer me representations of women, but items in whose creation women were active agents proved to be much scarcer than I had imagined. Finding objects created by non-elite women, or by women of colour from any class proved to be close to impossible.

On the other hand, what I did see was often much richer than I could ever have imagined. The Bodleian is not particularly well known, for example, for its women’s suffrage collection. As a suffrage historian myself, I had spent more time researching this field in the LSE’s Women’s Library than I had in Oxford. But, the Bodleian’s suffrage collection is in fact remarkably good, not least because it contains examples of most of the important sub genres within the field. I found postcards, petitions, minute books, handbills, posters, journals and much, much more. We managed to fill several cases with a wonderful array of suffrage materials, and what is now on display barely scratches the surface of what is available.

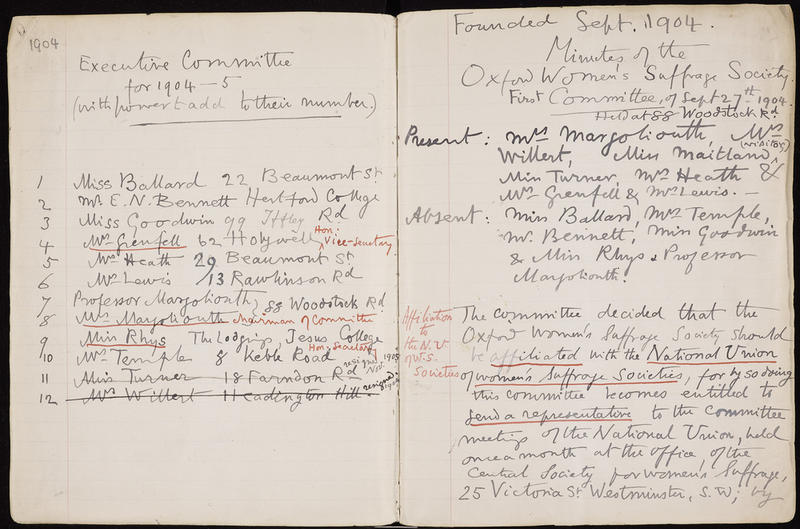

The Bodleian’s suffrage collection has not had the attention it deserves for a number of reasons. As one of the world’s greatest research libraries, the Bodleian holds a range of extraordinary collections in whose shadow most items would struggle to shine. The suffrage collection is relatively modern, some of it is printed and therefore available in other libraries, and its most interesting pieces are scattered throughout various collections and departments. But, there is more to it than this. It is a collection fundamentally made by and for women, and there is no central manuscript collection at its heart. The minute book of the Oxford Women’s Suffrage Society is one of the most exciting exhibits, not least because such regional records are exceedingly rare.

It is an extraordinary document which tells the story of a determined movement which incorporated town and gown, women and men and regional and national campaigning. It also reveals a good deal about university culture in the early twentieth century. It is held in the Deneke collection, an uncatalogued set of boxes which hold not only the minute book, but a range of suffrage and more broadly women-centered materials. The Deneke sisters were not Pankhursts or similarly well-known suffragists so their papers have escaped cataloguing. Their collection of Oxford-related suffrage ephemera is invaluable to the suffrage historian, but as the suffrage movement itself has not been afforded the significance it deserves by political historians of modern Britain, it has remained largely unstudied.

The format of many of the suffrage items in the exhibition pose their own challenges. Postcards, for example, are central to the suffrage display, but are not as obviously readable or authoritative as printed sources. Some of the postcards in our display, such as one of Clara Mordan, are exceptionally valuable in their own right as they are so rare, but they also collectively provide invaluable clues about strategy, fund raising, reach, marketing and suffrage tactics. They, like the many handbills and posters held in the Bodleian, can tell us about modes of organisation, about political education and about forms of political resistance. We must, however, be prepared to read them imaginatively and to take them seriously as sources. For example, two posters of women wanted by the police for suffrage militancy feature in the exhibition. They were filed by Bodley’s librarian in a folder entitled ‘Terrible Women’. In this instance, the cataloguing of the items is at least as interesting as the items themselves.

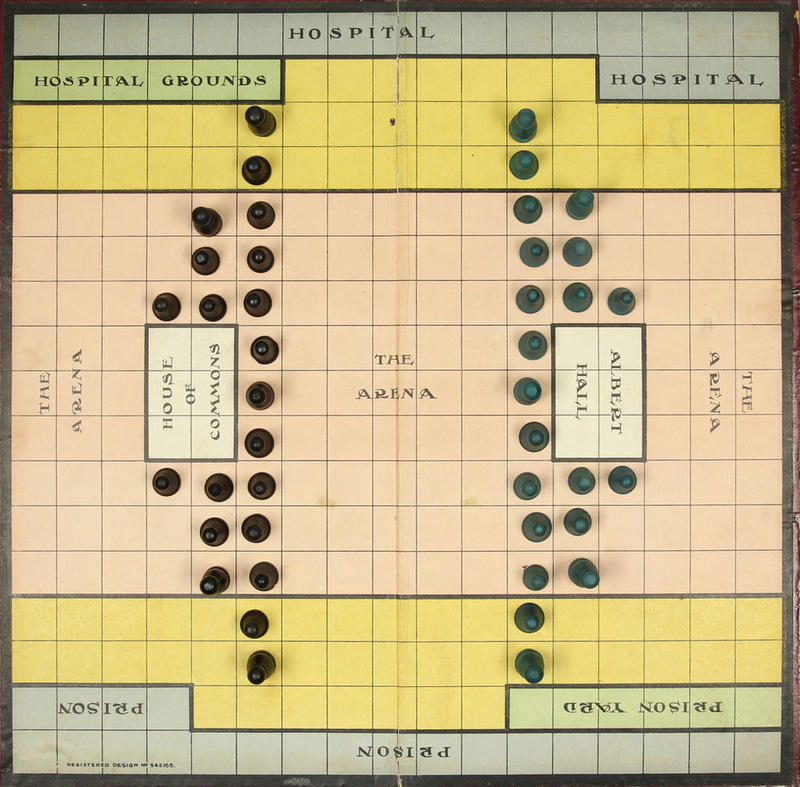

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Suffragetto, a board game made in around 1907.

Suffragetto is beautiful, it’s fun and it’s quite mysterious. We’re not entirely certain when it was made, how popular it was or why only one complete version of it seems to have survived. Yet, it tells us so much about the suffrage movement, more than any number of written records possibly could. As it was made for sale, we can infer that a market existed for suffrage paraphernalia. As playing it involves moving suffragettes and policemen to and from prison, the House of Commons, Albert Hall and the hospital around the board, we can assume that buyers were aware of suffrage strategies and the London locations which were central to their campaigns. It also reveals a great deal about the business side of suffrage, about the marketing and artistic skill of members, about their sense of humour and about the need to continue to raise cash for the movement. The fact that we know so little about a game which seemed to have run to more than one edition also suggests that there may well have been many other such items which have been lost to us. Made by women to fund a women’s political movement, its playful exterior masks a seriousness of purpose and determination. We are lucky to have it and I am not surprised that it has proved to be such an enormous hit.

There are many other wonderful items in the exhibition, each of which will encourage visitors to think not only about what women have done and achieved over the centuries, but also about how we and how our libraries collect and interpret the products of their labours. While we are of course exceptionally fortunate to have manuscripts by Jane Austen, Christine de Pizan and Mary Shelley, a first edition by Mary Wollstonecraft and a book made by Elizabeth I, we are equally fortunate to have records of pirates, of explorers, of criminals, of scientists and of printers. None of these items could be described as typical, or as having been made by ordinary women, but demonstrating the typicality of the women whose work has survived in the Bodleian is not what this exhibition is about. It is about showing how some women managed, often against enormous odds, to overcome two major barriers: the limitations to women’s freedom to produce and the general reluctance to collect or to preserve items made by women. Almost all of the women represented in the exhibition were white and privileged; such structural advantages are clearly grossly unfair, but also partly account for the production and survival of these items. Acknowledging this does not make up for the deep sense of regret over the lack of diversity in the Treasures Gallery. But, it does encourage us to think about how and why some items survived, and to acknowledge that collecting, preserving and displaying are products of their own social and intellectual contexts, and drivers of them too.

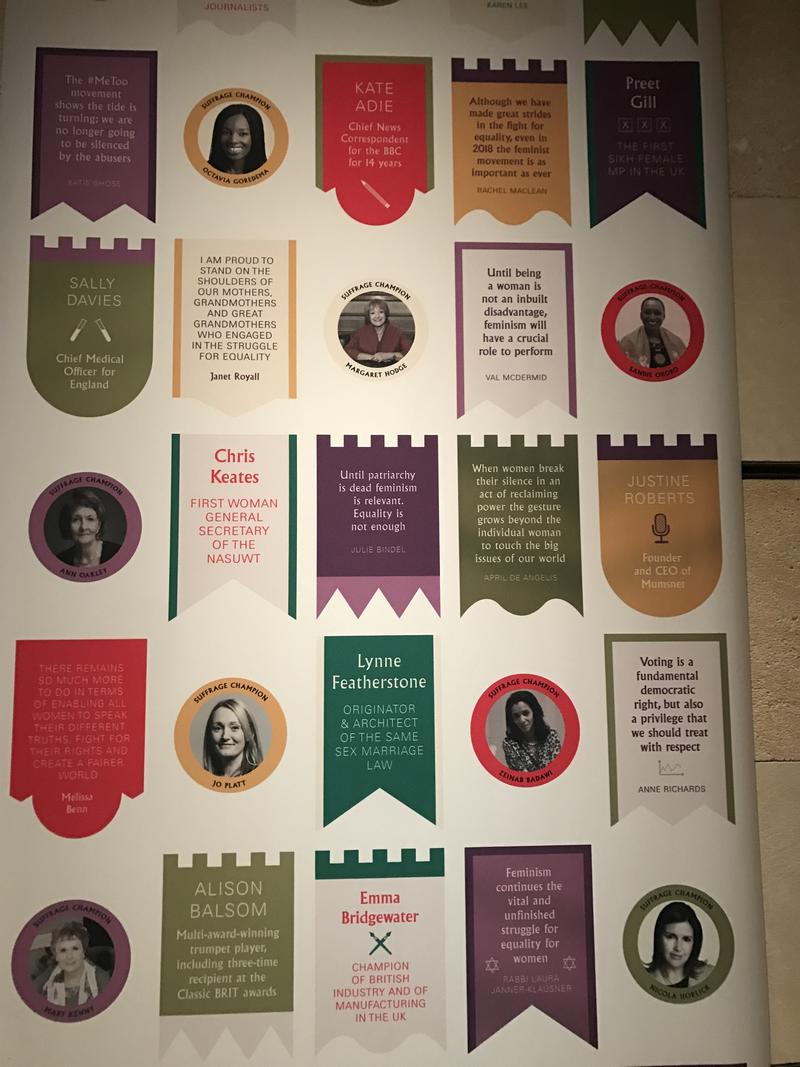

This exhibition marks the centenary of women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom; it is also concerned with highlighting the pioneering women who predated the suffrage movement and those who came after them. To this end, and to encourage visitors to reflect on continuities and change, we commissioned two new displays for the exhibition. The first is the ‘lost’ Oxford suffrage banner [https://wih.web.ox.ac.uk/article/lost-banner] and the second is our modern suffrage wall. The latter features women from around the UK who represent a variety of occupations from within the Arts, Business, Education, Politics, Science and Sport.They were invited to become Women in the Humanities suffrage champions, and to reflect collectively on women's achievements and the continuing need to challenge barriers to gender equality. Their thoughts are arranged in the style and the colours of the banners carried by suffragists one hundred years ago.

Our display of modern suffrage champions mirrors the exhibition’s postcard display of the original suffragists whose campaign changed British political life profoundly one hundred years ago. In creating these new items for display, we have added to the Bodleian’s holdings by and about women and we have contributed to an ongoing and increasingly urgent debate about gender equality. Juxtaposing the original suffragists with the contemporary beneficiaries of their sacrifices allows us to reflect on what has changed in terms of the cultural and social backgrounds of prominent and campaigning women, on how far women have come, and on the extent to which the grievances articulated by women more than one hundred years ago remain relevant today. Exhibitions don’t change the world, but they can help to shape discussions, to focus minds and to remind us all that history doesn’t just happen. It is made as we live it and shaped by how we interpret it.