Religion and the Women's Colleges

Dr Laura Schwartz

Victorian Christianity, its debates and divisions, fundamentally shaped the Oxford women’s colleges and the lives of women students and tutors. The Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women (AEW) was formed in 1878 with the intention of establishing the first hall of residence, yet within a year it was irreconcilably split over whether this ought to be an Anglican or non-denominational institution. Those who supported the latter position (liberal Anglicans in the main, including Mary (Mrs Humphry) Ward and the philosopher TH Green) broke away to found Somerville, while the remaining majority established Lady Margaret Hall on a ‘definite’ Church basis.1

The Church of England had a long-standing and paradoxical relationship with 19th century campaigns for women’s higher education. It was home to some of the most outspoken critics of women’s entry into the universities2, yet helped to establish a number of girls’ secondary schools and three out of the four Oxford women’s colleges. St Hugh’s and then St Hilda’s were also Anglican establishments, while the Society of Oxford Home-Students (later St Anne’s) was spearheaded by other Anglican members of the AEW: Bertha Johnson and Annie Rogers.3 It was, in fact, the ambivalence of the Church towards women’s higher education that determined many aspects of the early women’s colleges’ identity.

Oxford’s Church of England educationalists were in part spurred to action by a desire to outflank non-denominational or, even worse, secular institutions (such as University College London) from attracting ‘advanced women’ away from the Established Church.4 In 1878 the heterodox preacher Moncure Conway (a friend of the Freethinking feminist Annie Besant, and founder of the National Secular Society Charles Bradlaugh) offered a large sum of money to establish a woman’s college in Oxford. Horrified at such a prospect, the more orthodox advocates of women’s education moved swiftly to forestall it by establishing Lady Margaret Hall.5 Similar concerns prompted Lady Margaret Hall’s first Principal, Elizabeth Wordsworth, to found St Hugh’s, which charged much lower fees so as to be accessible to the daughters of impoverished clergy who might otherwise be forced to attend non-Church institutions.6

Elizabeth Wordsworth and St Hugh’s first Principal, Annie Moberly, were the daughters of Bishops – an important stamp of respectability which served as their main qualification for their new roles. They navigated a careful course between conservative opponents in their own church and heterodox radicals at the other end of the spectrum, to fashion a vision of women’s education informed by a distinct current of Church of England feminism. In 1884 Wordsworth’s father, Christopher, preached a sermon affirming the Bible’s teaching on women’s subordination to man and condemning the competitive and ambitious ‘self display’ that he believed was encouraged by the newly professionalised girls’ schools when they entered their students into public examinations. Yet he also gave his blessing to his daughter’s project at Oxford, in the belief that what mattered was the kind of education that the new colleges provided, advocating the direction of intellectual endeavours towards spiritual rather than material ends. Ten years later Elizabeth Wordsworth delivered an Address to the Church Congress in which she elaborated upon this view of the 'First Principles in Women’s Education’. She too believed that women ought to be the helpmate of man, but that their spiritual duty went beyond the individual home to improving society at large. One of the most important reasons for educating women was to enable them to become better religious teachers and equip them to defend the Church against secularising forces. Wordsworth and Moberly believed that women’s intellectual development ought only to occur as part of their spiritual development – their education must be about far more than passing examinations.7 Dorothea Beale, founder of St Hilda’s, shared this view: ‘I want none to go [to college]… merely for self-culture… but that they may do better service… for the glory of the Creator and the relief of man’s estate.’8 This approach led the Anglican colleges to favour a more flexible course of study for women students, diverging from the male curriculum, rather than seeking complete equality with Oxford men.9 Somerville, on the other hand, was the first women’s Hall to adopt a qualifying exam to candidates, to call itself a college and employ its own tutors on a more professional basis.10

While Lady Margaret Hall and St Hugh’s were embedded within the High Anglicanism that dominated Oxford at this time, and Somerville’s Council included members of a variety of views, the religious fervour that infused the movement for women’s education transcended theological and denominational divides. Almost all of its pioneers possessed a powerful personal faith and sense of spiritual and moral purpose that gave them the strength to face down opposition, redefine respectable femininity and dedicate long hours to nurturing these new institutions. Annie Moberly described religious feeling as ‘self-controlled vivacity of high spiritual existence…’. Theology was not a set of abstract principles or dry doctrines, but ‘a thrilling interest’ whereby one’s every movement, speech and thought was imbued with a sense of ‘unseen presences’.11 Sunday evening Bible classes and regular religious lectures led by the principals and resident tutors were also an opportunity for students to see female role models assume a position of cultural and intellectual authority at a time when women were barred not only from the Church hierarchy but also from Parliament and the majority of professions.

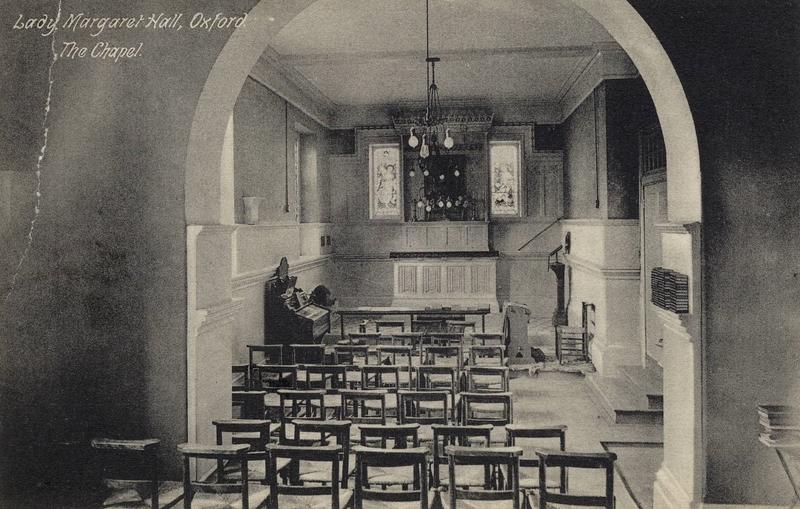

Christian worship structured students’ working day and the built environment in all of the Anglican women’s colleges. Attendance at daily morning and evening prayers was compulsory, and considerable resources were dedicated to constructing a college chapel where and, by the early 20th century, the women’s colleges were acquiring permanent buildings. This strong Anglican culture could be exclusionary, and ensured that only a narrow demographic of students felt welcome. Lady Margaret Hall had a conscience clause for its students, but nonetheless attracted few non-Anglicans, and in 1910 re-emphasised that all tutors should be members of the Church of England.12 St Hugh’s students did not have to pass a religious test but the College was advertised as being for Church of England students, and its first scholarships were open only to Anglican women.13 By contrast, Somerville’s non-denominationalism, and the fact that the Society for Oxford Home-Students allowed for its women to live semi-independently in private houses in the city, made them a more appealing choice not only for students of other Christian denominations but also for international students and those of different religions altogether. The Society for Oxford Home-Students included a number of Roman Catholics, still very much religious outsiders in a largely Protestant Britain, based in a hostel run by nuns at Cherwell Edge established in 1907.14 Somerville initially held morning prayers of a broad Christian character in its dining room, and when it finally did build a chapel in 1932 the College made sure to emphasise that it was open to all nationalities and religions.15 Bamba and Catherine Duleep Singh, British born but of the Sikh religion, became students there in 1890. Cornelia Sorabji, Somerville’s first Indian student, had arrived the year before. A Parsi Christian, Sorabji regularly attended church at St Giles, and her Christian friends provided an introduction into Oxford’s elite social circles. She was nevertheless rather taken aback to encounter many ‘old ladies’ keen to convert her, and when she reassured them that she was already of their faith they responded with surprise since she looked ‘so very heathen’.16

[1] 'Somerville College', in H.E. Salter & Mary D Lobel (eds.) A History of the County of Oxford: volume 3, The University of Oxford, (London, 1954), 343-347. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp343-347 [accessed 18 March 2020]; Pauline Adams, Somerville for Women: an Oxford college 1879-1993 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); Janet Howarth, 'The Church of England and women's higher education, c. 1840-1914', in Peter Ghosh and Lawrence Goldman (eds.), Politics and Culture in Victorian Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 153-170.

[2] Howarth, 'The Church of England', p. 153, 166; John William Burgon, To Educate Young Women like Young Men, And with Young Men, – A Thing In Expedient and Immodest: a Sermon Preached before the University of Oxford in the Chapel of New College on Trinity Sunday (June 8th, 1884) (Oxford & London: Parker & Co., 1884).

[3] R. F. Butler & M. H. Prichard (eds.), The Society of Oxford Home-Students: Retrospects and Recollections (1879–1921) (Oxford: The Oxonian Press, 1930).

[4] Howarth, 'The Church of England'.

[5] Georgina Battiscombe, Reluctant Pioneer: A Life of Elizabeth Wordsworth (London: Constable, 1978), p.64.

[6] Betty Kemp, 'The Early History of St Hugh's', in Penny Griffin (ed.), St Hugh's: 100 Years of Women's Education in Oxford (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1986), 15-47.

[7] Christopher Wordsworth, Christian Womanhood and Christian Sovereignty: a Sermon (London: Rivington's, 1884); Elizabeth Wordsworth, First Principles in Women's Education (Oxford: James Parker & Co., 1894); Laura Schwartz, A Serious Endeavour: Gender, Education and Community at St Hugh's, 1886-2011 (London: Profile Books, 2011), chapter 1.

[8] 'St Hilda's College', in H.E. Salter & Mary D Lobel (eds.) A History of the County of Oxford: volume 3, The University of Oxford (London, 1954), 348-350. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp348-350 [accessed 18 March 2020].

[9] Laura Schwartz, 'Feminist Thinking on Education in Victorian England', Oxford Review of Education, 37: 5 (2011), 669-682.

[10] Adams, Somerville for Women.

[11] Schwartz, A Serious Endeavour, pp.20-21.

[12] Howarth, 'The Church of England', p.160.

[13] Schwartz, A Serious Endeavour, p.25.

[14] H.E. Salter & Mary D. Lobel (eds.), 'St. Anne's College', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, The University of Oxford, (London, 1954), 351-353; Janet Howarth, ‘Johnson [née Todd], Bertha Jane (1846–1927)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: online edition, 2004)

[15] Daniel Moulin-Stozek & Fiona Gatty 'A House of Prayer for All Peoples: The Unique Case of Somerville College Oxford' Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Beliefs, 14:1 (2018), 83-114.

[16] Suparna Gooptu, Cornelia Sorabji: India's Pioneering Woman Lawyer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p.53.