Everyday Life

Jane Robinson

A villa in leafy Norham Gardens, an old stone house overlooking fields off the Woodstock Road and an elegant dwelling by the river in Cowley Place: any of these might be suitable to host a Victorian house-party. And in a way, that’s just what they did. When LMH, Somerville and St Hilda’s opened their doors in these three locations, prospective students were encouraged to think of their impending residence as an extended stay with respectable friends.

This aura of domestic gentility was something of a Trojan horse. It comforted parents warned by doctors that their daughters’ intellectual ambition would lead to infertility or chronic spinsterhood. It also reassured unsympathetic academics. As one of the founders of LMH put it: it was important that ‘nothing should happen in any way to make [male] college authorities anxious, or to strengthen the very decided initial prejudice of the undergraduates against supposed ‘bluestockings’… invading Oxford.’1 If female students looked as though they were spending the day chatting inconsequentially and sipping tea, they might be left alone.

In reality, everyday life in the women’s colleges was a curiously hybrid routine. Like house-guests, students were expected to dress for dinner; make polite conversation; not to speak to someone until properly introduced, and even then, not to use Christian names until invited to do so after weeks of familiarity.

This could lead to awkwardness – especially if one had never actually been to a house-party. When Jessie Emmerson arrived at St Hugh’s Hall in 1886, more modestly situated in a semi in Norham Road, she was unsure how to behave. ‘We all felt rather shy,’ she remembered, ‘especially during the first meals in the little dining room which looked into a small back garden containing nothing in particular except grass. But next door there were some rabbits in a hutch, and they at once arrested our attention and naturally became a subject of conversation when other topics failed.’2 Discuss rabbits was possibly not what she had come to Oxford to do.

The college houses, and later their bespoke buildings, were furnished in refined – if slightly shabby - style. Students were encouraged to enjoy the grounds, interact with the pets (St Hilda’s had kittens and Somerville, a donkey called Nobby), and be polite to the domestic staff.3 However, an almost conventual level of protection rendered these scholarly guests more like members of a religious community than friends of the family, and there was no escaping the bells, constantly reminding them of school.

Gradually, a modus vivendi was achieved, recognisable across the residential colleges.4 The day started at 7 am, when the scout arrived with hot water for washing (in a tin bath) and coal for the grate. Prayers were next. The whole college community gathered together, including servants, and the Principal presided. Breakfast was substantial. The morning was spent in study, lectures or tutorials until lunch at 1 pm.

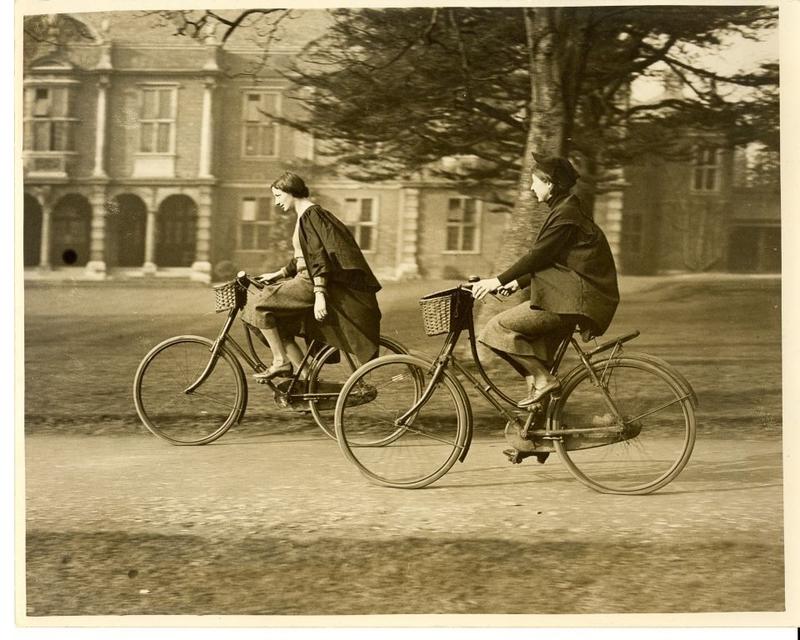

Exercise was encouraged during the afternoon. A photograph in the collections of St Anne’s – then the Society of Home Students – shows a group of women by the river in 1899, displaying a bewildering array of sports equipment. There is a boat with oarswomen (fully-dressed, of course, with collars, ties and hats); a few bicycles; any number of tennis racquets; what looks as though it might be a golf club, and a lacrosse stick. One maverick student stands defiantly holding a couple of scholarly-looking volumes, obviously wishing she were somewhere else.

More work followed until it was time to dress for dinner, which was always formal and involved a selected student mortifyingly having to ‘walk in’ the Head of House and sit next to her, making erudite conversation. Clubs and societies happened after the meal, with private visits to one-another’s rooms, cocoa-parties and fire-drill. Each of the colleges had its own fire-brigade, with equipment operated by the students. A cup of tea and slices of bread and butter were offered before lights-out at 11 pm.

Essays were posted to out-of-college tutors: it was quicker to mail them than to take them (which in the early days one couldn’t do without a chaperone anyway). Lectures were challenging, because they meant mixing to a limited extent with male undergraduates who might be offensive, defensive, lewd - or irresistible. Tutorials were similarly risky, even within college walls, with academic staff running the gamut between perfectly normal and reasonable people, to eccentrics of the first water.

Saturdays were more sociable and might include a visit to the theatre, if one could afford the necessary chaperone; there was church on Sundays, perhaps a longer walk in Port Meadow or a cycle-ride to Bagley Woods, and the inevitable task of multiple letter-writing.

These letters, now cherished by families and archivists, reveal the preoccupations of daily life. Apart from work and the pleasures and perils of friendship, the discussion of menus fills page after page. And so we get to the heart of daily life in college: food. It would be invidious here to identify the worst kitchens, but the best – according to student Ina Brooksbank writing in 1917 – belonged to St Hugh’s.5

For breakfast there was porridge, bread, butter, jam and marmalade, boiled ham, the occasional sausage, fish, fried or scrambled eggs on toast, and on Sundays, kidneys ‘with lovely thick gravy.’ For lunch: cold meat or a pie, liver, fish or hash (re-cooked, chopped meat and potatoes) with rice, sago or suet pudding with jam, or stewed fruit, with a cup of tea. Bread and margarine were served at 4 p.m. with another cup of tea, then came dinner, the highlight of the day. The first course usually involved ‘soups of various kinds from white to black’; there was a choice of main courses with potatoes and vegetables, including pork and beans, curried rice, vegetable hash, stuffed tomatoes or fishcakes. Dessert might be banana trifle, fruit tart, tinned pineapple or fresh apples and pears.

If this was the fare during the First World War, what would it be in peace-time? The staff at St Hugh’s were wise. It was not always easy being a female student at Oxford. There would always be day-to-day problems to face, but a good meal with friends made everything seem better.

[1] Bertha Johnson, quoted in Gemma Bailey (ed.), Lady Margaret Hall: A Short History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923), p. 48.

[2] Jessie Emmerson’s reminiscences, published in the St Hugh’s College Chronicle (1931), St Hugh’s College Archives.

[3] A photograph of St Hilda’s students taken in 1907 includes at least one tabby kitten being cuddled. St Hilda’s College Archives.

[4] The following ‘day in the life’ is abstracted from the reminiscences of Frances Sheldon of Somerville (Somerville College Archives) and others featured in Jane Robinson, Bluestockings: the Remarkable Story of the First Women to Fight for an Education (Penguin: 2010).

[5] Ina Brooksbank reminiscences, St. Hugh’s College Archives.