Painting the Pioneers: Portraits of Women at Oxford

Dr Imogen Tedbury

Walk into any of the women’s colleges at Oxford, and sooner or later you will encounter the earliest pioneers in women’s higher education, immortalised in paint. These portraits were crowd-funded and commissioned by alumnae groups, staff and students to commemorate history through the ‘portrait transaction’, that is, the negotiation between sitter, maker, conventions and commission.[1] Painted to commemorate the principals, tutors and supporters of these colleges, these portraits were intended as symbols of collective identity, college traditions and institutional continuity.[2]

George Percy Jacomb-Hood, Madeleine Shaw-Lefevre, 1890. Oil on canvas, 118 x 89 cm. Gift from the Council and Students, 1890. Somerville College, Oxford.

The earliest paintings indicate the quasi-maternal role played by early college leaders, who were appointed as wardens with administrative and pastoral care duties. Some of these women, such as the first Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Elizabeth Wordsworth (1840-1932) or the first Principal of Somerville College, Oxford, Madeleine Shaw-Lefevre (1835-1914) had not had a university education themselves.[3] Shaw-Lefevre was appointed in part for her social work, her connections and her credentials as a respectable, cultivated woman, ‘the very antipodes of the clumsy, masculine blue-stocking’, as Wordsworth put it.[4] An alumna of Somerville noted that Shaw-Lefevre’s charm was ‘invaluable in disarming the hostile criticism with which the foundation of a woman’s college in Oxford was greeted from many quarters’.[5] Portraits of this generation of leaders present their sitters as demurely yet finely dressed elegant women, seated within artistic domestic interiors.

James Jebusa Shannon, Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth, 1891. Oil on canvas, 125 x 100 cm. Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

George Percy Jacomb-Hood’s Portrait of Madeleine Shaw-Lefevre (1890) and James Jebusa Shannon’s Portrait of Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth (1891) exemplify this trend. In Jacomb-Hood’s portrait, Shaw-Lefevre wears a black satin evening dress, with fur wrap and translucent lace gloves, resting her chin in one hand, books visible on the shelf behind her. Her portrait, completed in eight weeks, after three or four sittings a week, captures a thoughtful grace, inquiring and listening.[6] Wordsworth sits for Shannon in a similarly elegant interior, wearing a grey satin and embroidered tea gown, with a bowl of irises at her elbow. Both Jacomb-Hood and Shannon were renowned society portrait painters, who charged great sums for their sought-after portraits. Both painters were members of the New English Art Club, a group of artists who experimented with French modernism.[7] Loose brushwork brings a shining delicacy to both women’s dresses in these portraits: a conservative approach to their subject is paired with innovative painting technique. These portraits would have been recognisably fashionable in style – and recognisably costly as a financial outlay – to prospective students and their parents, promoting an impression of the college as an elite institution, comparable to the older men’s colleges.

After James Jebusa Shannon, Portrait of Dorothea Beale. Oil on canvas, 124 x 99 cm. St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

Shannon painted a number of portraits for early British women’s colleges in the 1890s, including Royal Holloway College and Newnham College as well as St Hilda’s College, where a copy of his portrait of Dorothea Beale still hangs today.[8] Colleges looked to each other for inspiration when searching for possible artists to undertake these important commissions. Correspondence held at Lady Margaret Hall relating to the search for an artist to paint former principal, Lynda Grier (1880-1967), reflects an earlier practice. In this, the painter was chosen collaboratively by sitter and portrait committee, who relied on the sharing of knowledge across the Oxbridge women’s colleges at meetings of the Association of Headmistresses and Principals, as well as visits to the Royal Academy to assess portraits on display in the annual Summer Exhibition.[9]

Samuel Henry William Llewellyn, Charlotte Anne Moberly. Oil on canvas, 75 x 61 cm. St Hugh’s Hall, Oxford.

The colleges sometimes appointed Academicians to undertake their portraits, such as Samuel Henry William Llewellyn (1858-1941), later the President of the Royal Academy (1928-38), who painted Charlotte Anne Moberly (1846-1937), the first Principal of St Hugh’s Hall.[10] Moberly’s frothy lace sleeves, a delicate pendant and the small posy pinned to her chest soften the severity of her high-necked black dress, wire-rimmed spectacles and simply styled hair. Seated against a painted landscape, Moberly occupies a liminal space, between interior and exterior, the natural world and the artificial, as Llewellyn chooses to play down Moberly’s academic credentials in favour of emphasis on feminine respectability.

Lowes Cato Dickinson, Clara Pater, 1860. Oil on canvas, 80 x 62 cm. Somerville College, Oxford.

In addition to commissioned portraits, the women’s colleges also received and displayed a number of donated portraits, depicting famous students, tutors and founders. In 1896, after Vice Principal Clara Pater (1841-1910) left Somerville for King’s College London, subscribers purchased and presented Lowes Cato Dickinson’s rather girlish portrait of her, which had been painted nearly 40 years earlier.

John Jackson, Mary Somerville as a Young Woman. Oil on canvas, 58 x 47 cm. Somerville College, Oxford.

Herbert James Gunn, Agnes Catherine Maitland. Oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm. Somerville College, Oxford.

The colleges also received gifts from external donors, such as Pre-Raphaelite painter and art dealer Charles Fairfax Murray’s donation of John Jackson’s Mary Somerville as a Young Woman.[11] Murray gave many of his English portraits to the Fitzwilliam Museum, but museum director Sydney Cockerell guided this gift to Somerville in 1911.[12] The portrait is now displayed in an ornate frame, set in the panelling of the college dining hall.

In a sense, the history of women’s college portraits runs parallel to the development of women’s college buildings. Portraits commemorate particular people and eras in college history, but they also function as interior decoration, indicative of colleges’ wealth and status, presenting a quasi ‘gallery of ancestors’ constructed from a uniquely female lineage. On occasion, additions to this lineage were made several years after a subject had left her position at the college. Agnes Maitland (1889-1906), second Principal of Somerville College, died in post in 1906.[13] Her posthumous portrait was undertaken by Herbert James Gunn, who painted her from photographs, and was only given to the college by bequest from Mrs Scoresby Routledge in 1937.[14] Catherine Ouless’s portrait of Esther Burrows, Principal of St Hilda’s College (1893-1910), was only painted in 1927, towards the end of the principalship of Winifred H. Moberly (1919-28), whom Ouless also painted for the college in 1929.[15] Ouless’s small oil sketch for Burrows’ portrait is also held at St Hilda’s today.

Catherine Ouless, Esther Burrows, 1927. Oil on canvas, 70 x 60 cm. St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

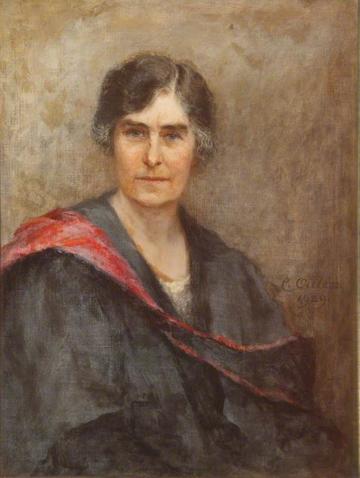

Catherine Ouless, Winifred H. Moberly, 1929. Oil on canvas, 72 x 57 cm. St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

Catherine Ouless (1879-1961) was unusual among the portrait painters commissioned by the committees and networks associated with the early women’s colleges, which often appointed well-known portraitists who regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy. Ouless herself usually painted landscapes, but she was the eldest daughter of a successful society portrait painter, Walter William Ouless (1848-1933), with whom she occasionally collaborated as a portraitist, for example in their 1925 portrait of Andrew Carnegie (National Galleries Scotland). This may have helped her win the two St Hilda’s commissions.[16]

The contrast between Ouless’s two portraits for the college, of Esther Burrows and Winifred H. Moberly, demonstrate the differences between the first and second generations of leaders at women’s colleges. Burrows’s gentility is emphasised by her delicate lace shawl and jewel at her throat, a three-quarter-profile portrait set in an oval frame. By contrast, Moberly is presented off-centre, clad in her Oxford MA hood, looking assertively at the viewer.

Unknown artist, Christine Burrows, c. 1920. Oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm. St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

A portrait of Christine Burrows (1872-1959), Esther’s daughter who held the Principalship following her mother and before Moberly, combines the softness of the former with the assertion of the latter.[17] Wearing a black velvet choker and jewel that seems to be the same one worn by her mother, she is presented in a commanding profile view, holding a book and wearing the crimson hood and gown of the Oxford MA, dating the portrait to after 1920.

Philip de László, Henrietta Jex-Blake, 1921. Oil on canvas, 90 x 69.5 cm. Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

Principals like Moberly and Christine Burrows had studied at university themselves, but had only recently been granted their degrees and the sartorial regalia associated with those degrees, after Oxford opened degrees to women in October 1920. Prior to this date, women like Emily Penrose (1858-1942), who had studied at Somerville before becoming principal there (1907-26), had opted to receive their degrees from Trinity College Dublin under the ad eundam agreement between the universities.[18] Her portrait by Philip de László, painted for Royal Holloway College in 1907, records her appearance wearing Trinity’s distinctive blue hood.[19] This portrait was the first of many De László would paint for the women’s colleges, including a portrait of Lady Margaret Hall’s Principal Henrietta Jex-Blake (1862-1953) wearing her new Oxford MA hood in 1921, and a portrait of Dr A. Maude Royden, a preacher and campaigner for the ordination of women whose portrait was donated to her alma mater, Lady Margaret Hall.[20]

Philip de László, Dr A. Maude Royden, 1932. Oil on canvas, 132.5 x 98.4 cm. Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

De László’s portraits draw on earlier portraiture traditions to present women wearing academic dress in a distinctly feminine manner. Like Emily Penrose, these sitters wear their university hoods askew across the upper body like a sash, or the drapery of neoclassical dress, but if anything they are more feminine in appearance than the statuesque, standing Penrose, recalling more closely the portraits of enlightenment intellectuals from the Bluestockings Circle, such as Robert Edge Pine’s painting of Catherine MacCaulay, née Sawbridge, or Catherine Read’s portrait of Elizabeth Carter.[21]

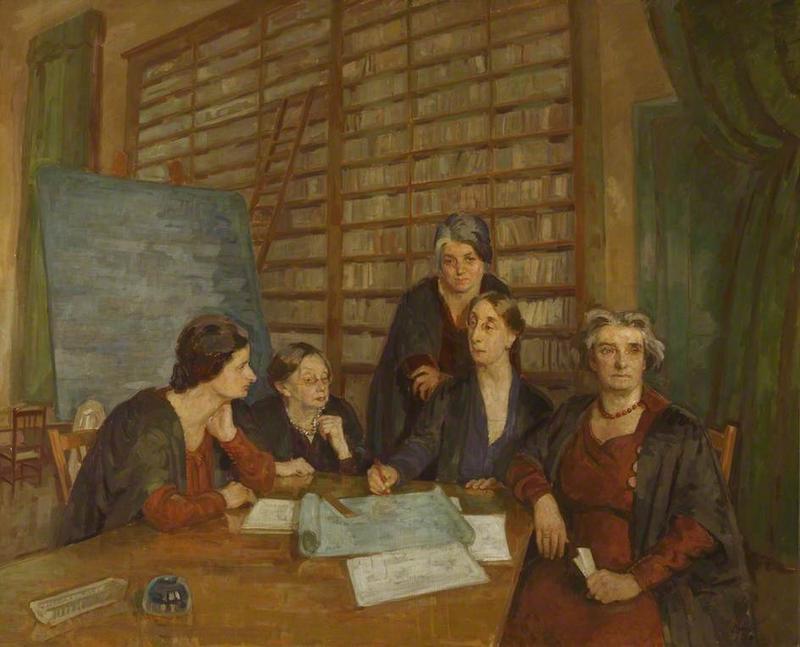

Henry Lamb, Group Portrait, 1936. Oil on canvas, 100 x 120 cm. St Hugh’s College, Oxford.

Just this handful of examples demonstrates how the formal portraits commissioned by the early women’s colleges at Oxford speak to inherent tensions surrounding women’s education in the years before and after women first received their degrees in 1920. In many ways these portraits exemplify the conservatism and caution of the colleges more generally. As Martha Vicinus put it, this caution ‘locked women into a rigid mould of respectability, when they might have gained more by daring more’.[22] Portraits were often commissioned from respected, known artists, whose work was recognisable as a financial investment. These portraits were initially conventional in composition and sitters’ dress, with little to distinguish them from the family portraiture of the day.[23] Yet later artists such as De László developed new portrait types, which presented these distinguished women wearing academic dress, drawing on neo-classical traditions to recall female figures like the sibyls and the muses, thus rooting a radical subject in respectability. By the 1930s, women wearing academic gowns had become a kind of uniform, as recorded by Henry Taylor Lamb’s Group Portrait of five Fellows of St Hugh’s.