Libraries for Women Students

Duncan Jones

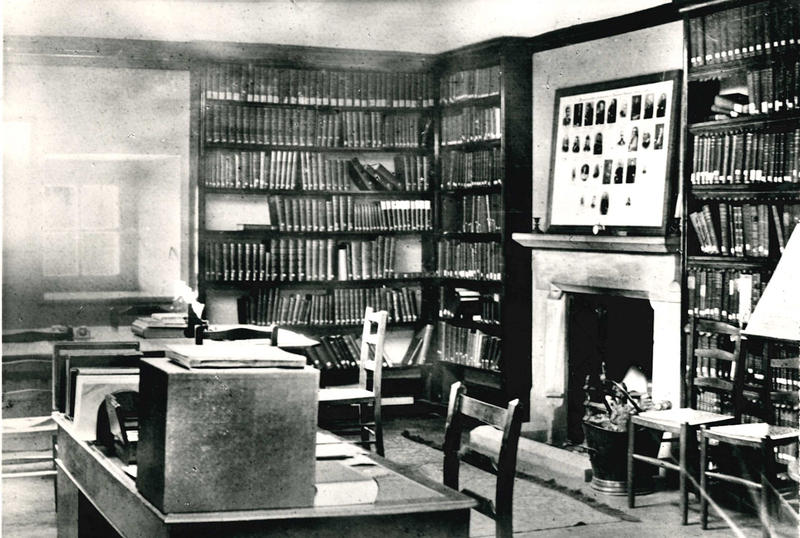

Nettleship Library, 1898

In the 21st Century, the libraries of the former women’s colleges number among the largest and most well stocked of any college in Oxford: a 2017 survey showing that all five were among the top ten libraries by modern collection size. The prevailing narrative is that this size is a reaction to early women students having been excluded from the Bodleian Library.[1][2] In fact, there were many contributing factors to college library growth and the Bodleian Library and Radcliffe Camera were among the few libraries that women students could access from the very beginnings of their Oxford education.

For the first two hundred and fifty years of its existence, the Bodleian had been a place for graduates, fellows and visiting scholars.[3] From the mid 19th Century it was open to anyone with “a proper introduction”[4] and, indeed, as early as the 1860s women scholars such as Agnes Strickland[5] and Mary Arnold[6] were granted access. Undergraduates, who at that time were exclusively male, were not admitted until 1856 when statutes were altered.[7] What is now the Old Bodleian’s Upper Reading Room was then a picture gallery[8] and the Lower Reading Room functioned more as a stack than a study space, this being available only in the central bays and ‘Seldon End’ of Duke Humfrey’s Library. In 1860 the Radcliffe trustees offered the Radcliffe Camera to the Bodleian and it was soon converted into an undergraduate reading room, with the first floor opening to students from 10am to 10pm daily the following year.[9][10] The ground floor was at first enclosed as a book stack, but this too was quickly turned over to further study space as student numbers rose.[11] In 1855 there had been just 16 Bodleian Library readers per day but by 1876 it was 130 and in the winter of 1880 there were a record 275.[12] A printed catalogue and a carefully selected students’ library of 6,000 reference works were added in the 1880s.[13][14] The memoir of a female student writing in 1888 recalls taking leave of her chaperone to study at one of the designated tables in the Camera for the use of women students, having been granted a reading order by her principal.[15]

Access to the Bodleian’s collections was a boon to the women student and the male undergraduate alike, since the latter could expect little provision from his own college’s library. Access to these varied and was certainly improving towards the end of the century but many college libraries were the preserve of fellows who allowed their students in only by special arrangement. At extreme ends were University College which had had a separate undergraduate library by 1862 and Oriel, which until 1902 offered only a cupboard full of books.[16][17] In fact, undergraduate libraries in the men’s colleges were so few and far between that the future Bodley’s Librarian, E. B. Nicholson, claimed in 1879 to have never heard of one.[18]

Therefore, purely in terms of access to research collections of the Bodleian and core texts of the Camera, women students of the newly emerging halls and societies were on a relatively even footing. What they did lack compared to the men though, were lending collections. The Taylor Institution Library admitted any paying reader but would lend its books only to members of the University.[19] Most department and faculty libraries were established after the 1877 University Reform Act, with many opening in the years leading up to the First World War,[20] but women students, who were not officially part of the University or attached to any faculty, were excluded from these collections. As Arthur Sidgwick wrote in a petition to the Hebdomadal Council in 1895 “as compared with undergraduates they are in every way at a disadvantage”.[21]

The great lending library of 19th Century Oxford was the Oxford Union Society Library;[22] its former librarian describing it as the “one library used by the great mass of undergraduates” and with a circulation on par with all the other University libraries put together.[23] There may be some exaggeration in this, but the Union Society Library was certainly the principal supplier of undergraduate texts in 19th Century Oxford.[24] Although Union membership was closed to women until 1963 the librarian had actually proposed library access for women students in 1879,[25] specifically to allow the women of Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall to borrow books until their own hall libraries were more developed.[26] The motion was carried successfully (254 votes to 238) despite fervent opposition from such figures as George Curzon who, somewhat ironically, became a key ally to the degree movement when he was made Chancellor of the University 30 years later. The closeness of the vote and obvious hostility alongside coverage in the national press brought unwanted attention and additional controversy to the women’s education movement in Oxford at its fragile beginnings. Mindful of this, a decision was taken to politely decline access to the Union Library.[27]

It was natural then, that library collections should form at the women’s halls for their own dedicated use and to facilitate borrowing among women students. The organic growth of these collections and of the circumstances of living and teaching meant that the libraries were initially crammed into the cupboards, hallways and assorted living spaces of the various old houses where the halls had invariably begun.[28]

It was at Somerville that the first purpose-built library of a women’s hall was constructed, being completed in 1903 and opened by the Vice-Chancellor and other dignitaries the following year.[29] St Hilda’s followed suit in 1909,[30] Lady Margaret Hall in 1910[31] and St Hugh’s in 1916.[32] Many women read towards examinations in English Literature or Modern Languages which were only established as Honour Schools at the University in 1897 and 1903 respectively.[33] As such, few of the men’s colleges or the departments and faculties had strong libraries, or indeed any libraries, to support teaching in these areas. Somerville’s library was perhaps the first of any college in Oxford to have been built with the student, and not the fellow, at the forefront.[34][35] The women’s halls and societies could establish their libraries to support teaching from the get-go and once their buildings were completed, had the space, if not always the funds, to do so.

On completion, Somerville’s 26,000 capacity library had just 6,000 volumes.[36] Gifts and donations were an essential part of the growth of library collections for women and were actively solicited for.[37] Somerville had received 400 books from the widow of Mark Pattison in 1884, and its new building was followed by two major donations: the books and papers of Egyptologist Amelia B. Edwards and those of John Stuart Mill. The former prompted the construction of an additional room and the latter was absorbed into the working collection and increased its size by nearly one third.[38] Elizabeth Wordsworth’s memoir recalls the importance of donations for the development of Lady Margaret Hall’s library with gifts from publishers, private individuals (including John Ruskin) and other institutions, notably Newnham College.[39] Clara Evelyn Mordan’s 252 book bequest and donation in 1915 led to the new library being named after her at St Hugh’s[40] while Dorothea Beale’s library formed the genesis of the rare book collection at St Hilda’s. It was common across all of the halls for students to donate a book as they left Oxford and for tutors to make bequests or gifts of their own collections.

These college libraries were not the only lending resource available to women. Matilda Nettleship, widow of Henry Nettleship, donated her late husband’s classics books to the A.E.W. (Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women) in 1895 to be a lending library for all women students.[41] As the A.E.W. had an office in the attics of the Clarendon Building, it was here that the first 750 or so books came to rest; a combination of Nettleship's library and additional volumes bought with donations in his memory. Though almost entirely classics books to begin with, this new shared lending library soon became a valuable resource for all women students. It was staffed for borrowing in the mornings and open for reference access into the afternoon.[42] By the end of the 1895-6 academic year, the collection had grown through philanthropy to 986 volumes and the librarians of Lady Margaret Hall, Somerville and St Hugh’s had been elected to the library committee.[43] Further growth was supported by the A.E.W.’s general fund and the payment of ’returned fees’ by students attending lectures.[44] An assistant librarian was appointed in 1897 and by 1900 the A.E.W. office was overflowing with over 3,000 books.[45]

At the same time, willingness to share the Bodleian and its study spaces was wearing thin among some Oxford men. A letter to the Oxford Magazine in 1900, entitled 'Overcrowding of the Bodleian by Women' complained that the women students used it as a waiting room between lectures and contrasted them with the “genuine” researchers who were trying to work alongside them. The letter writer acknowledges the need for a central space more convenient than the distant halls and implies that the Camera was by this time already overrun with women and undergraduates.[46] Annie Rogers wrote of being present in the Nettleship Library when it was inspected by the Vice Chancellor and other senior officials but said that "it was no doubt easier to complain of women readers crowding the Camera than to take steps to make the Nettleship Library of greater use”.[47]

Happily, a central study space was soon found to alleviate further conflict; a large room adjoining the existing A.E.W. office made available and fitted out with chairs and tables with pots of ink.[48] The new Reading Room doubled the available space and allowed the library to house bulky reference collections such as the Dictionary of National Biography, the use of which had been one of the main reasons for women to visit the Bodleian.[49]

Finances at the A.E.W. and in the women’s societies were tight around the turn of the century[50] and so, with stretched book budgets in the 1905-6 academic year, the librarians of each society agreed to open their science collections to all A.E.W. registered students.[51] This meant not only offering borrowing access to collections but also guaranteeing a minimum spend on science books and focussing on a given field so that even coverage was provided. Somerville would buy Physics and Chemistry; Lady Margaret Hall would specialise in Zoology and Physiology, St Hugh’s in Geology, and St Hilda’s in Botany, while the Nettleship would largely carry periodicals. A similar proposal in 1871 by the Oriel historian James Bryce for the men’s college libraries to choose a subject specialism and open their doors to the wider student body had been “wrecked on the rocks of college independence”.[52] The collaborative nature of women’s education was a sturdier platform from which to launch such a shared enterprise and indeed the scheme operated in one form or another until 1960.[53]

Further college collaboration was heralded by an announcement in the June 1915 edition of The Fritillary which declared the opening of the Inter-Collegiate Library of Modern Literature. Accessible for a terminal subscription of 1s. 6d. and initially housed at the Home-Students common room on Ship Street, the student led library was intended to supplement the college libraries and Nettleship by carrying the sort of popular fiction not held there.[54]

In 1915, Somerville found its premises in demand as an extension of the Radcliffe Infirmary and patriotically vacated them, moving wholesale to Oriel’s St Mary Hall quad. The library was the exception to this relocation and continued to be accessed throughout the war.[55] In 1916, the report from the Committee on the Napier Memorial Library Fund announced that it had secured enough funding to purchase the library of the late Professor Napier for the benefit of undergraduates and registered women students reading for English.[56] The natural place for such a collection to reside would be at Acland House, with the rest of the English School’s library (established in 1914), though at the time this was a collection closed to women. The Assistant Registrar wrote to Miss Burrows (Principal of St Hilda’s) in the same year agreeing to open the library to women students reading English.[57] Such arrangements were easier to instigate under the turmoil of war but carried with them the proviso that they could revert when normality resumed. The minute books of the Nettleship Library indicate that staffing was in short supply in the University and that any objection would be more likely to be against increased demands on time rather than the presence of the women themselves.[58] Attitudes were certainly easing, but the committee still felt it necessary to enquire whether tutors and research students would also be admitted.

By 1920 the books, staffing and opening hours had all steadily increased at the Nettleship and in that year there were 8,500 volumes with 4,159 term time loans and 2,100 in the vacation.[59] The degree question and the 1920 changes to statutes had little discernable impact on the growth of women’s library collections, though women could now access many Oxford libraries on the same terms as the male undergraduates. The principals of the societies wrote an appeal to the April 1920 Royal Commission for financial support; with the war over and the A.E.W. set to be disbanded, they asked for finances for both the extension and maintenance of their hall libraries and for central accommodation for the Nettleship Library alongside activities such as lectures and administration. Interestingly, the primary reason given was “in view of the distance at which the women’s Colleges are situated from the centre of Oxford.”[60] Though access to the University’s libraries had been available in one form or other for some time, it had been granted with a reluctance that could make women students feel like outsiders. Even in 1927, when numbers of women students were limited by a statute, one of the arguments given was over the competition for places in libraries.[61] It is little wonder that women wished to consolidate their own collections outside of the jurisdiction of the University and the atmosphere of opposition.

The Nettleship Library was eventually transferred to the Society of Oxford Home-Students in 1934 but the Geldart Law Library (established 1921) operated as a shared resource for women law students as late as 1978.[62] The attitudes of independence and the focus on practical teaching collections continued to pervade the women’s colleges for the decades up to and beyond the eventual co-educational movements of the later 20th Century. For the fellows and tutors who had studied in a time of exclusion, where resources had to be bargained for and carefully managed, the library remained an important focal point in the college design.

Annexes:

Librarians

Lady Margaret Hall

| 1879–1893 |

Elizabeth Wordsworth |

| 1894–1902 | Eleanor Constance Lodge |

| 1902–1907 | Agnes Muriel Clay |

| 1907–1921 | Evelyn Mary Jamison |

Nettleship

| 1895–1897 | S. Gurney |

| 1897–1889 | Elinor R. Price |

| 1889–1914 | Frances M. Wells |

| 1914–1918 | E. M. Moore |

| 1918–1937 | Dorothy M. Bigg |

Somerville

| 1885–1887 | Isabella Don (also English Tutor, she became Principal of Aberdare Hall, Cardiff in 1887) |

| 1892 | F. Butlin |

| 1892 | Creation of a Tutorship with additional responsibility for the library and to assist the Principal with secretarial work |

| 1893 |

Library Committee formed consisting of four members within the Hall and one outside member. Miss Pope appointed as Library Secretary for one year (in June 1893); short-lived title, by October she is referred to as the Librarian. |

| 1893–1899 | Mildred Pope* (Alice Bruce Secretary and Sub-Librarian from 1894) |

| 1896–1899 |

Alice Bruce also listed as Librarian with Mildred Pope * Mildred Pope was Tutor in Modern Languages from 1894-1934 |

| 1899–1904 | S. Margery Fry |

| 1904–1905 | Rose Sidgwick (also temporary Tutor in History) |

| 1905–1907 | Mildred Pope Librarian; Lucy Kempson Sub-Librarian |

| 1907–1914 | Lucy Kempson (also Principal’s Secretary) – to end MT 1914 |

| 1915 | Madeline Giles, Librarian and Principal’s Secretary, HT & ET/TT 1915 |

| 1915–1928 | Vera Farnell (also Principal’s Secretary 1915-19; Dean 1924-47; Assistant Tutor in Modern Languages 1920-34) |

St Hilda’s

| 1893–1908 | Christine M. E. Burrows (effectively) |

| 1908–1912 | Margaret Adele Keeling (also English Tutor) |

| 1912–1920 | Louisa Fentham Todd |

| 1920–1922 | Eleanor Willoughby Rooke |

St Hugh’s

| 1895–1896 | M. L. Lee |

| 1896–1899 | E. M. Venables |

| 1899 | Margaret Hayes-Robinson |

| 1899–1901 | D. Wylie |

| 1902–1902 | W. Mammatt |

| 1902–1904 | Eleanor Frances Jourdain |

| 1904–1913 | Helena Clara Deneke |

| 1913–1917 | E. M. Thomas |

| 1917–1922 | Dame Joan Evans |

Library Volumes by Academic Year

|

|

Lady Margaret Hall |

Nettleship |

Somerville |

St Hilda’s |

St Hugh’s |

|

1894–1895 |

|

750 |

|

|

|

|

1895–1896 |

|

986 |

|

|

|

|

1896–1897 |

|

1130 |

|

|

1000+ |

|

1897–1898 |

|

2047 |

|

|

|

|

1898–1899 |

|

2416 |

|

|

|

|

1899–1900 |

|

2900~ |

|

|

|

|

1901–1902 |

|

3300~ |

|

|

|

|

1902–1903 |

|

3900~ |

|

|

|

|

1903–1904 |

|

4143~ |

|

|

|

|

1904–1905 |

|

|

6000~ |

|

2000+ |

|

1905–1906 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1906–1907 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1907–1908 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1908–1909 |

|

5158 |

|

|

|

|

1909–1910 |

|

5455 |

|

|

|

|

1910–1911 |

|

5740 |

|

|

|

|

1911–1912 |

|

6000~ |

|

|

|

|

1912–1913 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1913–1914 |

|

6853 |

|

|

|

|

1914–1915 |

|

7284 |

|

|

|

|

1915–1916 |

|

7504 |

|

|

|

|

1916–1917 |

|

7701 |

|

|

|

|

1917–1918 |

|

7858 |

|

|

|

|

1918–1919 |

|

8111 |

|

|

5000~ |

|

1919–1920 |

|

8466 |

|

|

|

[1] Somerville College, About the Library. Available at: https://www.some.ox.ac.uk/about/the-library/about-the-library Accessed 5th May 2022. “The long, narrow building was designed specifically to provide enough storage so that Somerville students would not be disadvantaged by their lack of access to the Bodleian.”

[2] Lady Margaret Hall, Library. Available at: https://www.lmh.ox.ac.uk/about-lmh/lmh-library Accessed 29th June 2022. “Women were not allowed to use the Bodleian Libraries up until the 1920s”

[3] H. H. E. Craster, History of the Bodleian Library, 1845-1945 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1952), p. 24.

[4] E. C. Thomas, “The Libraries of Oxford, and the uses of College Libraries” Transactions and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom : Held at Oxford, October 1, 2, 3, 1878 (London : Strassburg: Trübner and, 57 and 59, Ludgate Hill ; Karl I. Trübner, 1879), p.25.

[5] U. Pope-Hennessy, Agnes Strickland, Biographer of the Queens of England, 1796-1874 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1940), p. 274.

[6] J. Sutherland, "A Girl in the Bodleian: Mary Ward's Room of Her Own" Browning Institute Studies 16 (1988) pp. 169-80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25057834

[7] G. Barber, Arks for Learning : A Short History of Oxford Library Buildings (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1995), Occasional Publication (Oxford Bibliographical Society) ; No. 25 [i.e. 26], p. 21.

[8] H. H. E. Craster, History of the Bodleian Library, 1845-1945 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1952), p. 9.

[9] R. H. Hill, The Bodleian since 1882 : Some Records and Reminiscences (London: Printed by Headley Brothers, 1940), p. 6.

[10] P. Morgan, “Books for the Yonguer [sic] Sort : Oxford Undergraduates and Their Books from Stuart to Modern times” Antiquarian Book Monthly Review (Oxford : AMBR, 1976), p.120.

[11] G. Barber, Arks for Learning : A Short History of Oxford Library Buildings (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1995), Occasional Publication (Oxford Bibliographical Society) ; No. 25 [i.e. 26], p. 21.

[12] P. Morgan, “Books for the Yonguer [sic] Sort : Oxford Undergraduates and Their Books from Stuart to Modern times” Antiquarian Book Monthly Review (Oxford : AMBR, 1976), p.120.

[13] R. H. Hill, The Bodleian since 1882 : Some Records and Reminiscences (London: Printed by Headley Brothers, 1940), p. 6.

[14] E. C. Thomas, “The Libraries of Oxford, and the uses of College Libraries” Transactions and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom : Held at Oxford, October 1, 2, 3, 1878 (London : Strassburg: Trübner and, 57 and 59, Ludgate Hill ; Karl I. Trübner, 1879), p.26.

[15] A Lady Undergraduate, “A Day of her Life at Oxford” Murray's magazine : a home and colonial periodical for the general reader (London : John Murray, 1888), 3, 17, p.684

[16] G. Barber, Arks for Learning : A Short History of Oxford Library Buildings (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1995), Occasional Publication (Oxford Bibliographical Society) ; No. 25 [i.e. 26], pp. 22-23.

[17] P. Morgan, “Books for the Yonguer [sic] Sort : Oxford Undergraduates and Their Books from Stuart to Modern times” Antiquarian Book Monthly Review (Oxford : AMBR, 1976), p.121.

[18] E. C. Thomas & H. Tedder, Transactions and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom : Held at Oxford, October 1, 2, 3, 1878 (London : Strassburg: Trübner and, 57 and 59, Ludgate Hill ; Karl I. Trübner, 1879), p.125.

[19] E. C. Thomas, “The Libraries of Oxford, and the uses of College Libraries” Transactions and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom : Held at Oxford, October 1, 2, 3, 1878 (London : Strassburg: Trübner and, 57 and 59, Ludgate Hill ; Karl I. Trübner, 1879), p.26.

[20] G. Barber, Arks for Learning : A Short History of Oxford Library Buildings (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1995), Occasional Publication (Oxford Bibliographical Society) ; No. 25 [i.e. 26], p. 24.

[21] For the Hebdomadal Council only. [Petition for a grant of books to the A.E.W. 23rd May, 1895] [St Anne’s College Archive, W.S. 2/1]

[22] P. Morgan “Oxford libraries outside the Bodleian” Bulletin // Ligue des Bibliothèques Européennes de Recherche, (Florence, 1986), LIBER – 17, The libraries of Oxford, pp. 5-7.

[23] E. C. Thomas, “The Libraries of Oxford, and the uses of College Libraries” Transactions and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom : Held at Oxford, October 1, 2, 3, 1878 (London : Strassburg: Trübner and, 57 and 59, Ludgate Hill ; Karl I. Trübner, 1879), p.26.

[24] G. Barber, Arks for Learning : A Short History of Oxford Library Buildings (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1995), Occasional Publication (Oxford Bibliographical Society) ; No. 25 [i.e. 26], p. 22.

[25] J. Howarth, “’In Oxford...but not of Oxford’ : The Women’s Colleges” The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VII: Nineteenth-Century Oxford, Part 2. (Oxford University Press). Retrieved 6 October 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/97....

[26] E. T. Cook, Oxford Union Society [Poll], November 15th 1879 [Somerville College Log Book Volume 1, Somerville College Archive]

[27] J. Howarth, “’In Oxford...but not of Oxford’ : The Women’s Colleges” The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VII: Nineteenth-Century Oxford, Part 2. (Oxford University Press). Retrieved 6 October 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/97....

[28] F. Dolman, “Women’s Colleges at Oxford” English Illustrated Magazine, (January 1897) pp. 460-1 https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/07030a4c-4209-45d7-95e3-e2d9a50bb3f9/surfaces/e455eb90-7e46-4309-a7ca-652686d05825/)

[29] J. G. Batson, Her Oxford (Nashville : Vanderbilt University Press, 2008), p. 80

[30] St Hilda’s College, St Hilda’s College: A Concise History, (2020), p. 15 https://issuu.com/sthildascollege8/docs/st_hilda_s_history

[31] J. Howarth, “’In Oxford...but not of Oxford’ : The Women’s Colleges” The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VII: Nineteenth-Century Oxford, Part 2. (Oxford University Press). Retrieved 6 October 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/97....

[32] St Hugh’s College, History of the Library. Available at: https://www.st-hughs.ox.ac.uk/current-students/library/ Accessed 21st October 2021.

[33] P. Adams “’A Voice and Physiognomy of their Own’ : The Libraries of the Oxford Women's Colleges” Oxford Magazine, (Oxford, 1996), 134, p. 8

[34] P. Adams, Somerville for Women: An Oxford College 1879-1993 (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996) pp. 64-67

[35] P. Morgan, Oxford Libraries Outside The Bodleian: A Guide, (Oxford : Bodleian Library, 1980), p. 135

[36] P. Adams “’A Voice and Physiognomy of their Own’ : The Libraries of the Oxford Women's Colleges” Oxford Magazine, (Oxford, 1996), 134, p. 6

[37] P. Adams “’A Voice and Physiognomy of their Own’ : The Libraries of the Oxford Women's Colleges” Oxford Magazine, (Oxford, 1996), 134, p. 7

[38] P. Adams, Somerville for Women: An Oxford College 1879-1993 (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 64-67

[39] E. Wordsworth, Glimpses of the Past (London : A. R. Mowbray, 1913), p. 160.

[40] St Hugh’s College, College Report, 1915-1916, p. 8. https://issuu.com/sthughscollegeoxford/docs/r-1-1-1915

[41] A. M. A. H. Rogers, Degrees By Degrees (Oxford, 1938), p. 62.

[42] The Fritillary (Oxford, 1894-), December 1895, p. 103

[43] The Association for Promoting the Education of Women in Oxford : Report, October 1895 – October 1896, pp. 9-10 [St Anne’s College Archive, A.E.W. 1/1A]

[44] A. M. A. H. Rogers, Degrees By Degrees (Oxford, 1938), p. 129

[45] The Fritillary (Oxford, 1894-), March 1900, pp. 313-4

[46] L. N. T. “Overcrowding of the Bodleian by Women” Oxford Magazine (Oxford, 1900), 18, pp. 393-394

[47] A. M. A. H. Rogers, Degrees By Degrees (Oxford, 1938), p. 130

[48] St Hugh’s College, St Hugh’s Club Paper (1898-), 6, January 1901 https://issuu.com/sthughscollegeoxford/docs/club_paper_issue_6

[49] L. N. T. “Overcrowding of the Bodleian by Women” Oxford Magazine (Oxford, 1900), 18, pp. 393-394

[50] The Association for Promoting the Education of Women in Oxford : Report, October 1903 – October 1904, p. 9 [St Anne’s College Archive, A.E.W. 1/1A]

[51] Regulations for borrowing Science Books [St Anne's College Archive]

[52] P. Morgan, “Books for the Yonguer [sic] Sort : Oxford Undergraduates and Their Books from Stuart to Modern times” Antiquarian Book Monthly Review (Oxford : AMBR, 1976), p.120.

[53] P. Adams “’A Voice and Physiognomy of their Own’ : The Libraries of the Oxford Women's Colleges” Oxford Magazine, (Oxford, 1996), 134, p. 9

[54] The Fritillary (Oxford, 1894-), June 1915, p. 31

[55] P. Adams, Somerville for Women: An Oxford College 1879-1993 (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996) p. 89

[56] The Napier Memorial Library Fund: Report of the Committee. Committee of English Studies for the Board of the Faculty of Mediaeval and Modern Languages. Oxford, November 11, 1916. [St Anne’s College Archive, O.U. 5/1]

[57] Letter from E.S. Craig to Miss Burrows dated 13th November 1916 [St Anne’s College Archive, O.U. 5/2]

[58] Minute Book, Nettleship Library, A.E.W. February 1916—February 1933 [St Anne’s College Archive]

[59] A. M. A. H. Rogers, Degrees By Degrees (Oxford, 1938), p. 130

[60] Untitled Appeal to the Royal Commission, April 1920 [St Anne’s College Archive, W.S. 7/1]

[61] P. Adams “’A Voice and Physiognomy of their Own’ : The Libraries of the Oxford Women's Colleges” Oxford Magazine, (Oxford, 1996), 134, p. 7

[62] P. Morgan, Oxford Libraries Outside The Bodleian: A Guide, (Oxford : Bodleian Library, 1980), p. 11